The Centre Pompidou announces its first collection of NFT and NFT-related artwork, featuring art by Jonas Lund, curated to ‘reflect the astonishing wealth of the forms of artistic creation associated with blockchain’.

THE CENTRE POMPIDOU IN THE AGE OF NFTs

As 2023 kicks off, the Centre Pompidou is the very first institution dedicated to modern and contemporary art to acquire a group of works dealing with the relations between blockchain and artistic creation, including its first NFTs. In all, eighteen projects by thirteen French and international artists are joining the collection. Produced by a variety of practices and cultures, such as crypto art, the plastic arts and new media, these works reflect the astonishing wealth of the forms of artistic creation associated with blockchain. Discussion by Marcella Lista and Philippe Bettinelli, curators of the video, audio and new media collection.

The Musée national d’art moderne (French Museum of Modern Art) has just included its first NFTs in its collection, along with a group of digital works dealing with the relations between blockchain and artistic creation. Among the thirteen artists selected for this ambitious acquisition project, we find the pioneers Claude Closky and Fred Forest, along with emerging talents like Chinese artist aaajiao, French artists Émilie Brout and Maxime Marion, and even Larva Labs, the American duo behind the “CryptoPunks” phenomenon, which popularised the very principle of NFTs with the general public.

As a sign of the times, in 2023 the acronym NFT (for Non-Fungible Token) entered the Larousse dictionary. But what is an NFT? As certificates of authenticity guaranteed by the blockchain system (a networked data storage technology comparable to a shared, decentralised and encrypted ledger), NFTs are unique by definition. And it is this unique character that explains the preference for using NFTs as certificates or deeds of ownership for digital goods, including artworks. Blockchains (whose emergence can be dated to 2008) have considerably marked the ecosystem of digital art, both in terms of the production and circulation of artworks. In the last three years, NFTs have thus stimulated a digital art market that is more volatile than ever. The bubble burst in the wake of spectacular transactions (the most famous still being by American artist Beeple who, in March 2021, sold his digital collage Everydays: the First 5000 Days for $69.3 million). The cryptocurrency market (on which the NFT market depends) has experienced a marked downturn, notably with the crash of the FTX assets exchange platform in late 2022.

As a sign of the times, in 2023 the acronym NFT (for Non-Fungible Token) entered the Larousse dictionary.

With this new acquisition, the idea is not so much to focus on the pop culture phenomenon of “collectibles” (collections of images sold by NFT, such as “Bored Apes” or “CryptoPunks”) as to explore the most daring uses of this technology in order to engage, according to Marcella Lista and Philippe Bettinelli “ an original study of the ecosystem of the crypto-economy and its impact on the definitions and contours of artworks, creators, collections and the receiving public”. Decoding an acquisition project that is profoundly rooted in a genealogy of the dematerialisation of artworks.

NFTs, blockchains, what’s so interesting about them?

Philippe Bettinelli — The recent media hype accompanying the NFT craze may have given the impression that digital art had just been born, whereas it has existed since the 1960s in very experimental forms that were much less widely disseminated at the time. When I became interested in them ten years ago, I didn’t imagine there would be such a boom in the visibility of these practices. Part of the success of NFTs can be explained by the fact that digital artists can now dispense with the traditional intermediaries of the art world, such as galleries and contemporary art fairs. They’re in direct contact with their communities. On the whole, the blockchain technology can be used for lots of things, some of which are relevant for us as a museum, while others have economic, commercial or civic goals – a variety of situations that may be reminiscent of the potential of video… ranging from teleshopping to Nam June Paik ! This potential is already an interesting cultural phenomenon.

Marcella Lista — In the beginning, in the NFT ecosystem we witnessed the phenomenon of collectibles such as, for example, the famous “Bored Apes” and the “CryptoPunks”, which were the focus of intense media attention. Cultural production at the time was fairly homogeneous in its modalities. Then unique approaches appeared, opening up a critical space. “Bitchcoin” by Sarah Meyohas, for example, was launched in February 2015, thus before the Ethereum cryptocurrency. This community currently embodies some of the most stimulating artistic debates of the contemporary world.

How did you choose the artworks and the artists figuring in the list of acquisitions?

Marcella Lista — We explored three lines of approach. Crypto art, the emerging art form inspired by blockchain technology in which personages who are often not from the art world but from web design, music or text, express themselves – an interesting phenomenon that resonates with what happened in the early days of video. Then there are artists who have specifically explored the digital domain since the 1990s, initially in a marginal manner, and who currently receive more and more attention from institutions, critics and the market. Lastly, there are the visual artists from the world of contemporary art who pick up on the questions posed by blockchain.

Philippe Bettinelli — We were particularly interested in works dealing with transformations of the Net and of our digital world. Some cast a critical eye on the blockchain phenomenon or express a desire for transparency in transactions. Others explore the promise of inviolability of data or the issues associated with digital privatisation. Still others explore the technical and formal potential of these new technologies. We conducted major research and sorting work, the NFT ecosystem – which enables anyone to create a token – being very profuse by nature.

Why be the first French museum to acquire NFTs?

Marcella Lista — The idea was not to be the first but to bring together a meaningful collection that could testify to the critical and creative appropriation of a new technology by artists, and how that disrupts and shifts the art ecosystem. Since its inception, the Centre Pompidou has believed that contemporary technological creation and creativity should be at the heart of the institution. As early as 1972-1975, even before the Centre opened, the French Museum of Modern Art acquired major works and installations by Dan Graham and Bruce Naumann. Video installations using real time, and it was the very first institution to do so.

This was followed by numerous initiatives, such as the creation of the Revue virtuelle (Virtual Review) in the 1990s, on CD-ROM only, or the commissioning of the video and computer installation Zapping Zone by Chris Marker in 1989, and the Tunnel sous l’Atlantique (Tunnel under the Atlantic) by Maurice Benayoun in 1995… The new media collection was conceived as a forward-looking collection from the very beginning. Today’s acquisition of a group of NFTs by artists reflects current thinking on the museum’s collection.

How do NFTs fit into the history of art?

Marcella Lista — Many preoccupations pre-existing in the history of art reappear in the context of the blockchain. For example, Sentimentite, a work by Polish artist Agnieszka Kurant, looks at the forms of currencies that existed before money, and which continue to exist as clandestine and parallel currencies in all sorts of social microcosms. Others explore questions of copyright and law, like Jill Magid, who works on the idea of property and the intertwining of emotional, symbolic and financial values on the web. Some NFTs also fit into the tradition of computational art – John F. Simon and Larva Labs, for example, explicitly echo the earliest experiments with composition through calculation, which we find with François Morellet and the first users of computer software.

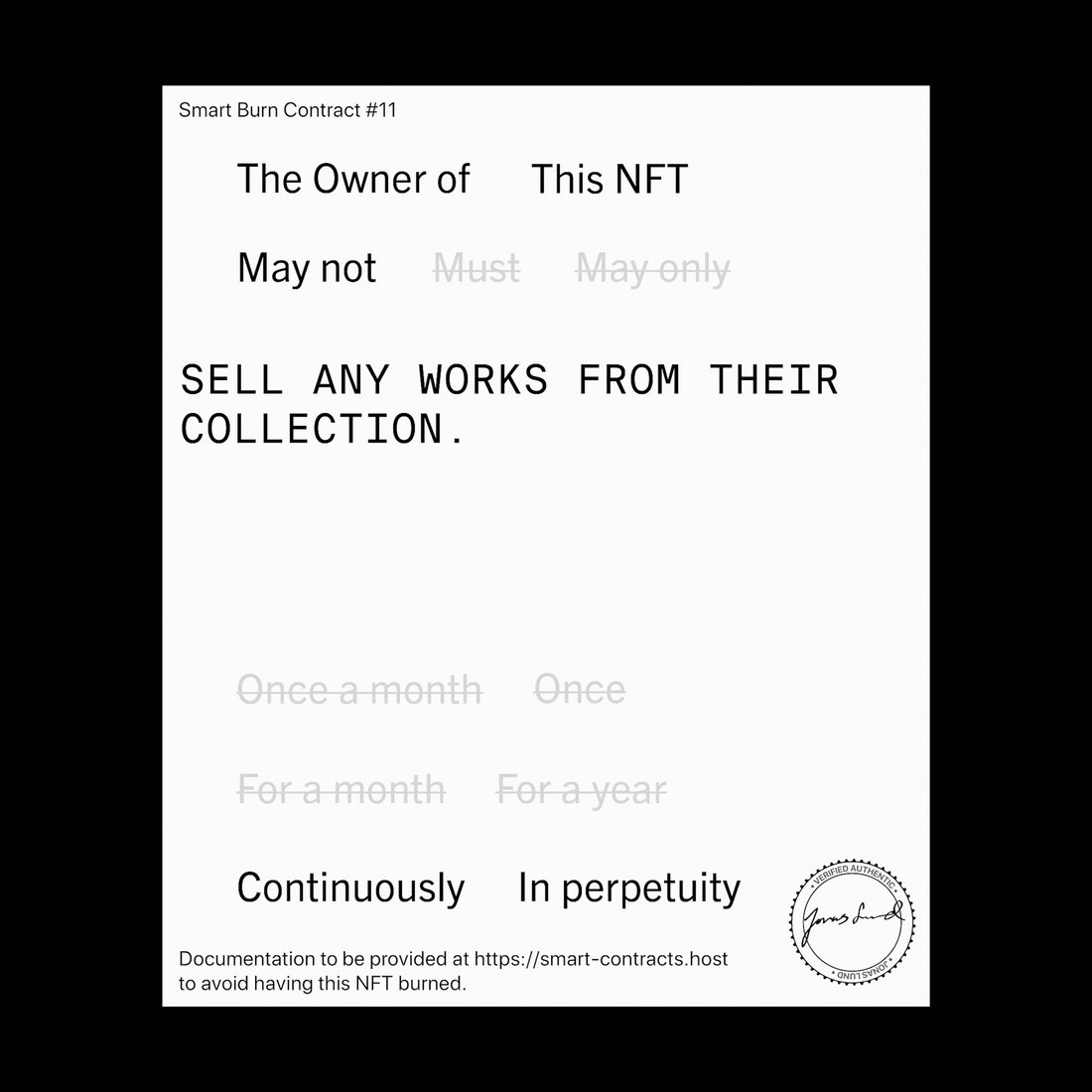

Philippe Bettinelli — Some pieces find their place in the ongoing history of “protocols” or “certificates”, which we find in conceptual and minimal art. Jonas Lund’s work entitled Smart Burn Contract (Hoarder), is thus a contract that the collector undertakes to respect. The Autoglyphes by Larva Labs play with a history of a work with a protocol.

NFTs are immaterial artworks, so how can they be owned and exhibited?

Philippe Bettinelli — We will soon be exhibiting these works. For the moment, most of them can be seen online, on the platforms that gave rise to them. For the exhibition, we will put them in context, notably by presenting some objects that testify to this history of the dematerialisation of artworks, such as certificates, protocols and documents that have accompanied immaterial procedures in modern and contemporary art since the second half of the 20th century – Chéquier by Yves Klein, for example. In terms of conservation, in general, new media artworks are subject to the risk of technological obsolescence. This holds true for the videos acquired in the 1960s and for the artists’ Internet sites purchased since the early 2000s. Our mission continues to be to ensure the transfer of works from a technology on the wane to a new one. While the medium is new, our methodology remains the same – many works being fixed images or video files accompanied by a token on the blockchain.

Marcella Lista — These forward-looking artworks, which contain a new model of materiality, represent fascinating challenges for us: it is up to us to find the administrative, legal and technical solutions in order to preserve them.