Claudia Hart, in discussion with Anika Meier in the third and final of three conversations for EXPANDED.ART, speaks about her journey from traditional medium to the world of virtual reality and NFTs, remarking on her background in architecture and her perception of the present.

CLAUDIA HART: ON VISION AND THE VISIONARY, CONVERSATION WITH ANIKA MEIER PART III, UNCANNY IMAGES AND SIMULATIONS

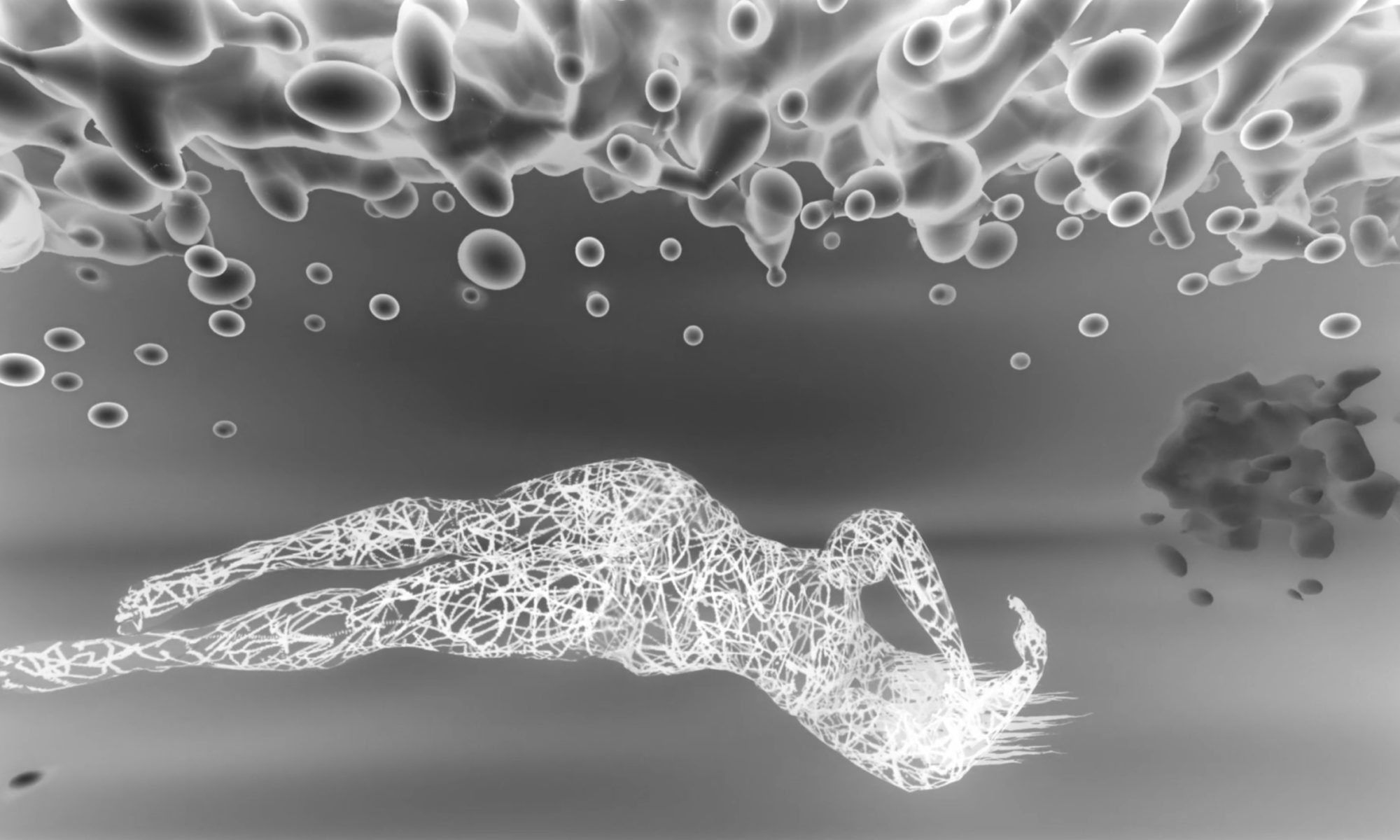

With a background in architecture and writing, Claudia Hart came into the spotlight in the 1990s as a multimedia artist interested in investigating themes of representation and identity. Hart integrates subjects from art history, philosophy, and cultural studies to examine themes of feminism, embodiment, and temporality through symbolic poetics that embroider onto real-world politics. She does this by drawing on computing, virtual imaging, and 3D animation technologies. No matter the medium, Hart has made a name for herself by creating uncanny, mesmerising images.

In the third and final of three conversations with Anika Meier for EXPANDED.ART, Hart speaks about her journey from painting to animation, virtual reality, and NFTs; her background in architecture and its influence on her practise of creating uncanny images; and how Hart, as an artist of our time, sees the present.

Anika Meier: You are known for creating uncanny images. How do you achieve this?

Claudia Hart: My 3D animations are driven by software processes mimicking natural forces, like wind rippling across trees and flowers or a body slowly growing old and wrinkled through the force of gravity. I often subvert these natural processes by directing them to perform in unnatural ways. These are the forces that we as human beings experience with our bodies in the tangible world in the course of everyday living. When I reduce gravity or dramatically speed up the breath of an avatar so that it is noticeably out of sync with the rustling of leaves, a viewer perceives this off-ness at the edge of their consciousness. When I layer many of these subtle a-synchronizations into a single animation, even when there is very little action otherwise, I create an uncanny image.

In THE SEASONS, a 12-minute 3D animation I made in 2007, I thought of myself as reimagining a classical sculpture of a seated woman, but a new version of sculpture that was simulated—one that existed in the unreal space and time only possible inside of a computer. Her body slowly melts, sunken by gravity as we all are when we age, ultimately decaying after we are dead and buried. We all experience this slowly, over the course of a human lifetime, but not in the course of an eleven-minute animation. At the same time, I also simulated roses that grew and then disintegrated, as they might over the course of a summer. And simultaneously, I simulated rocking my virtual camera. I moved it, as if it were hand-held, back and forth, always keeping it centered on the seated figure, so you could not really see any rocking, only perceive it at the edge of your consciousness. These contradictory rates and times confuse your mind and lull you into a reverie.

There is always something similarly strange and slightly off with all of my animations, but it is difficult to understand exactly what. One feels this strangeness with one’s body rather than through logic. It is perceptual and ends up being hypnotic and mesmerizing. A doctor friend once told me that medical hypnosis happens in the same way. A hypnotist asks their subject to focus on one thing, which is moving at a certain rate, while at the same time moving another object at a different rate. I started doing this with my first animations in the late 1980s. I knew they were fascinating because nothing much happened in them, but people would sit and stare at even a very short animation, looped ad infinitum.

This piece, MORE LIFE, was one of the first that I produced after the series of book works that I did in the early nineties. I consider it to be the beginning of my current installation-based 3D animation practice. It is only 30 seconds in length. I made it in 1998, but it was first shown in ANIMATIONS, curated by Carolyn Christov-Barkargiev (Christov-Bakargiev was Artistic Director of dOCUMENTA-13) and Larissa Harris at MoMA PS1 in 2001-2002, and later at Kunstwerke Berlin in 2003.

The presentation format for this work is a large TV placed on the floor in the corner of a dark room, mirroring the scene represented in the animation: a TV in the corner of a dark room displaying a stuffed bear, speaking in a corner of yet another dark room, standing in front of a TV in a dark room, also broadcasting the same talking head—a stuffed bear, speaking in a dark room. MORE LIFE is a recursive system, meaning a self-reflecting system, one that uses itself to build itself, just like those used in the programming languages of thinking machines like the computer. The soundtrack is an audio grab from the 1982 Ridley Scott film BLADE RUNNER. Hauer plays Roy Batty, an android programmed to live only a couple of years. So “I want more life, fucker,” is what Batty says before crushing the head of his creator, the director of a fictional computer multinational, the “Tyrell Corporation.”

In the same line is DREAM from 2009. It marks the start of my collaboration with the composer Edmund Campion, who is credited with being the first to use computers to collaborate with him in his creative process. Ed is also the director of the Centre for New Music and Audio Technology, a part of the University of California, Berkeley. I am a Fellow there and have been very involved with helping them set up their audio-visual doctoral programme. In this one, I slowly turn the camera 90 degrees as the figure drifts first from left to right and then vertically up, as if she were being sucked up a pipe. To do this, I changed the direction of gravity midcourse from moving in a horizontal direction to moving in a vertical direction. Both of these things create the kind of perceptual confusion that is hypnotic.

AM: You speak of animations. When looking at the history of art, where do you see yourself?

CH: I think of my work as simulated paintings, sculptures, and architecture. From the beginning, I wondered: if a building, a sculpture, or a painting were fake, how would they exist in time? What would it be like? Yes, it would be slow, and it would also be odd.

All 3D pictures are odd. They hover in an in-between liminal space between photographic capture and a perspective hand drawing. In school, I learned about and became fascinated by the development of perspective. I was particularly struck by drawings by the 18th-century “Visionary” architects making drawings during the period of the European Enlightenment, when data-based science as we now know it was forming. I studied art history at New York University with the art historian Robert Rosenblum. His seminal 1967 book TRANSFORMATIONS IN LATE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY ART had a lot of impact on me. Rosenblum introduced me to the European drawings of the Visionary “paper” architects of the 18th century. They never built; they only made drawings of fantastical buildings. Claude Nicolas Ledoux, Étienne-Louis Boullée, and Jean-Jacques Lequeu, who made what became known as “visionary” work because of technological advances in the science of perception, first made during the Renaissance, Rosenblum taught me about two-point perspective, developed in the 16th century by Albrecht Dürer, whose 1514 engraving MELANCHOLIA was the prototype for my own artistic identity.

I think there is a one-to-one relationship between the way we make pictures, the technology of the way we make them, and the way we do things in the tangible world. Building styles evolved because of the introduction of perspective. Architects discovered a new way of drawing that was more accurate and realistic, which was quite astonishing to the people at the time when it was new and strange. Perspective allowed them to imagine buildings in a different way. The visionary architects of the next century then produced engravings and drawings to portray new forms of architecture. They were fantastical and imaginative, but at the same time real.

It is no coincidence that these 18th-century works were also related to the “paper” architects that I studied with at Columbia University in the eighties, what they then called “propositional” architecture. The core group was called The New York Five and included Peter Eisenman, Michael Graves, Charles Gwathmey, John Hejduk, and Richard Meier, with associated others including Kenneth Frampton and Gwathmey’s partner Robert Siegel, who all taught at my school. Frampton was my advisor—the one who encouraged me to write and helped me publish my first essays. And, as I mentioned in one of the other interviews, artists like Dan Graham and Vito Acconci were also part of the same discussion. We were all looking at the Visionary architects, the most important to me being Jean-Jacques Lequeu, whose pornographic, self-referential drawings I assiduously copied when I first taught myself how to draw in the 1980s after deciding that I was NOT an architect but rather an artist. All of them produced radical architectures that seemed to exist in familiar but strangely unfamiliar worlds. All were men. My teachers. There were other young women also in the program, and we tried to drive a wedge into this male-dominated world.

The impact of the 18th-century Visionary architects that I learned about when I was in my early twenties still permeates my work. It’s like my artistic perfume. You can smell it in everything that I do. This was the invite card for EMPIRE, a four-channel animation that I made in 2009 and showed in a larger survey of my work from that period. It was curated by Murray Horne at the Wood Street Media Art Centre in Pittsburgh in 2010.

EMPIRE was inspired by the 1836 paintings of Hudson River School artist Thomas Cole’s series. The building is supported by a diverse group of Caryatids that slowly decay and grow moldy as the 10-minute animation transits from sunrise to sunset. This piece is based on CENOTAPH, a drawing by Étienne-Louis Boullée, the 18th-century French Visionary. I also included statues inspired by the Palaeolithic VENUS OF WILLENDORF figurine. The figures sink and decay; the color morphs from pink to blue, from sunrise to sunset, as the camera slowly zooms in, going to black and then restarting.

AM: How did architecture influence your animations later?

CH: From the beginning, I was inspired by the architectural design of the computer interface of my 3D animation software. I’ve used the same software since the very first art pieces I made in the nineties. I still work with it today. Part of it is the process I, as a user, enact whenever I make an image or an animation in 3D. I begin by building a model in an architectural game space. If I am not making an animation OF architecture, I still build one that I use as a kind of “virtual studio” in which I paint or design sculptures. But instead of using a pencil or cardboard, I always built them in Maya, my 3D animation software that I learned when it first came out in 1998.

The conceptual interface design of Maya was very important to the development of my art, in the same way that a camera profoundly affects a photographer. We artists all live inside our apparatuses. So when I build a world in Maya, I feel like I am an avatar constructing an environment in a computer game world. It is a strange experience because I have the illusion that I am physically building my worlds with my entire body, but instead I am actually holding a mouse and staring at a screen. I then paint my worlds, often “free-hand,” meaning by eye. But again, I am tangibly moving a mouse around on a table, staring at a screen, rather than holding a paintbrush in my hand and staring at a piece of stretched linen.

To heighten my own self-deception, I usually wrap my models (or what we call “texturing” in 3D-speak) with photographs of linen. I use a “watercoloring” computer tool that also simulates gravity. My fake watercolors appear to drip and spread. So even my simulated painting techniques mimic natural forces. What I do is not a tangible painting but, instead, an enactment. It is a simulated, virtual performance of art-making. I perform traditional painting or sculpting inside an artificial world. It is very bizarre and dreamlike. Even after the 25 years that I have used the same 3D software, it does feel supernatural to me. It is a dance between the real and the fake. My body dances with my simulation software. They meet in virtuality, in a choreographed conflict of opposites, creating strange but familiar works of uncanny beauty.

I very intentionally danced the dance of painting simulation in 2020, when I produced THE RUINS at bitforms gallery, New York. The show opened during the COVID quarantine. The installation included 3D animations. I tried to subvert my sculptural 3D animations to make them seem flat, again with the goal of creating perceptual confusion that would mesmerize and fascinate. These were very short animations inspired by Matisse paintings, including the ones pictured here: BIG RED (2019) and THE GREEN TABLE (2020). I wanted them to be ultra-short—only one minute. My goal was to make them hypnotic so that no one would notice how short they actually were. They should exist in an infinite present tense. To create the illusion, each animation included many floral arrangements, all moving at different rates, and organic noise patterns that also unfolded at varying speeds. It worked.

The Black Lives Matter movement was happening, and I felt that it was profoundly important. I was thinking about systemic collapse and showing the flow of history as a cycle of decay and regeneration. I imagined myself navigating out of the paradigm of a fixed photographic capture of the real into a reality of malleable and inherently unstable computer simulations and systemic collapse.

AM: During the pandemic, you also minted your first artworks.

CH: THE RUINS is a 3-channel animation. In it, I track through a claustrophobic, labyrinthian game world from which there is no escape. I imagined myself as an art forger, making illegal copies of paintings by Matisse, Picasso, and other patriarchs of the School of Paris. The joke was that these forgeries were actually virtual sculptures—3D computer models of their famous still-life paintings. This was how I started with NFTs. I wanted to mint my fake sculpture and fake painting forgeries to make them non-fungible. My blockchain contract would determine me to be an “Autour,” meaning a person with a powerful cultural signature—a status from which I was excluded because I have been a woman for my entire adult life. It’s still a problem due to my age. The digital art culture is youth culture, making it difficult for people over the age of 65, which I am well over.

I painted my models in the game space by eye, carefully imitating the brushstrokes made by the “masters.” It’s important that my work feels personal. The idea is that they should be understood as being made WITH a computer, not BY a computer—a kind of duet that is my life-long practice.

AM: Not being bound to one medium is an integral part of your evolution as an artist. So for you, the next logical step was to combine digital and physical artworks when minting?

CH: In 2021, post-pandemic and the explosion of NFT, I introduced a new hybrid art form, what I called the DIGITAL COMBINE, part handmade painting, part text (minted on the Blockchain as part of the NFT distributed contract). I was interviewed about it in OUTLAND, RIGHT CLICK SAVE, and FLASH ART at that time. I generally think of NFT as a bridge between the tangible world and the “Cloud,” our current reinterpretation of that which was formerly known as “Heaven.”

I appropriated the term combine from Robert Rauschenberg to propose an artistic genre in which a tangible work is united with an ephemeral one. Likewise, Rauschenberg’s radical version of expanded painting mixed sculptural and painted elements together into a single work. In my parallel construction, DIGITAL COMBINES pairs a painting with a text, minted on the blockchain as part of the NFT contract.

Simulation is at the heart of my painting production. In THE RUINS, an installation at bitforms, I produced an animation in which I imagined myself as a forger. For the tangible paintings, I continue with that narrative. I generate each unique work in my gameworld, producing a still life “by hand” in a game space. I then take hardwood panels with distinctive grains, tangibly hand-paint them, and then spray them with pure pigment in layers with a computer-driven airbrush machine. I then combine my “simulated” tangible paintings with a digital simulation—purely literary—that is then minted as an NFT as part of the blockchain certification. They are one.

AM: Is the technology you use an integral part of creating artwork to you?

CH: It is actually the software that I use that deeply inspires me. I have often written about and taught the philosophy that is embedded in my software. Because I live inside it for so many hours a day, both teaching it and producing work with it, I understand it as a parallel world that has driven my understanding of culture as it now stands. We all agree that western culture is liminal now. Meaning that it spans virtual spaces in the metaverse and the tangible world. When I animate in 3D, my hands and my head are in the cloud, and my body is on Earth.

AM: When we speak about your art, you use the word simulations often. How do you define simulations?

CH: I like to use the word simulation because I think of it more as a cultural term than a technical term. To backtrack again, Johannes Vermeer was my favorite painter as a child and remains so to this day because he is the master of strange enchanted worlds that are uncanny: both real and unreal at the same time. He painted his masterpieces between the mid-1660s and 1678, almost a hundred years before the visionary architects that I also love. Vermeer’s paintings had this subtle, artificial strangeness that I still adore. This is because of the early version of photography that he used to produce his paintings, what is called a camera obscura. This is a lens that Vermeer placed in a way to reflect his setting, which is then reflected upside down onto his painting surface. He then traced it. His paintings are therefore subtly distorted. I spent many hours alone in the Metropolitan Museum in New York when I was a child, much of it with Vermeer. I feel very connected to him. Vermeer’s pictures were pre-photographic, and mine are post-photographic. But instead of a photographic lens, I am enabled by the kind of virtual imagining that I first caught a glimpse of when I saw TOY STORY I at the Berlin Film Festival in 1995.

From the moment I saw TOY STORY, I was transformed. I needed to learn 3D animation, so I re-immigrated back to the USA to learn how to use the software, which was impossible to access at that time in Europe. Henceforth, my version of architecture has dematerialized. Using 3D software, I built computer models for imaginary doll-house worlds to then transform them into flickering animated projections, something like a stage set. My buildings became imaginary non-sites, both fantastical and hypnotic.

AM: The natural progression seems to be VR when it comes to worldbuilding. When did you start working with VR?

CH: VR image making is based on simulation technologies that model the real world, both mathematically and in terms of how the software interface functions. There are varieties of 3D software, but Maya, the one I use, is of a specific variety where the interface is designed to imitate all kinds of natural and phenomenal processes. The software itself uses many natural sciences to model the real world. I think of the interface design, meaning the windows that I look through to build, light, paint, and move the things I make, as a portal in which all of the windows are based on data culled from different branches of scientific knowledge.

I imagine the windows of my Maya software as a library of scientific knowledge. Interface windows peek into different physical sciences, using the data and language of different branches of science to make things happen. To me, it is magical. The software itself turns me into an alchemist. Maya is philosophical software. It is epistemological. All of its windows are actually gateways into different fields of scientific knowledge, and together, their design is a graphic expression of epistemology theory and the science of knowledge itself. In my imagination, Maya, the software (and Maya, the word, which means illusion), is like The Great Library of Alexandria from ancient Egypt, once one of the largest and most significant libraries of the ancient world.

At a certain point, I started to feel constricted by this legacy. I felt like I was stuck in my labyrinthine virtual library with no way out. In 2013, Alfredo Salazar Caro, a favorite former student, and his business partner Will Robinson invited me to participate in their first Dimoda exhibition, The Digital Museum of Digital Art, an Oculus intangible museum exhibiting installations made in software game space. I jumped at the opportunity.

DiMoDA is the first Oculus museum dedicated to commissioning, preserving, and exhibiting VR artworks. Alfredo and Will started it in 2013. Dimoda was staged all over the world, with gallery and museum exhibitions in New York, Miami, Chicago, Berlin, Düsseldorf, Dubai, and Bangkok, among others. I was in DiMoDA 1.0, which also included Jacolby Satterwhite, Tim Berresheim, and Aquanet 2001 (Gibrann Morgado and Salvador Loza). I had no idea how to build a game world at that point, but Will Robertson patiently taught me. I was stuck in what I thought of as a virtual underworld, so I was inspired by Lewis Carroll’s ALICE’S ADVENTURES IN WONDERLAND to build a VR game version for Oculus. In Lewis Carroll’s WONDERLAND, reason and unreason collide to unleash a child-like madness—not quite sweet but instead somewhat perverse and diabolical. So for DiModa, I built my first Alice garden, a larger-than-life flower architecture that shattered and reformed itself over and over. It was haunting and claustrophobic, magnified by the headset that you had to wear to enter it. That DiModa VR piece is now inoperable. The Unity software used to produce it has evolved to the point that this early example no longer opens.

Ultimately, working with living humans proves too difficult for me. I am what you call an introvert-extrovert, so my introverted artist self has to perform for my extrovert theater director self, which is ultimately exhausting. In the end, I prefer to be alone with my avatars. So as Alice unfolded, I decided to give up the live performances, and after making three over the course of four years, I decided to go back to my virtual cave. I used motion capture technology to do this, creating ALICE UNCHAINEDin 2018.

For my final ALICE, I worked with only two performers: Kristina Isabelle (with whom I collaborated on the 2014 ballet, THE DOLLS) and my personal trainer, the wrestler Isaias Valesquez. I motion-captured live performances made by each of us that we choreographed together. My friend, the producer Stephan Dalbera, a pioneer of mo-cap technology, hooked me up with a sophisticated commercial game company that supported the project. The technology had not gone mainstream at that point. The end result is a gender-fluid cyborg dance taking the form of a three-channel animation and VR-headset ballet. My grand finale was ALICE UNCHAINED. She was finally fully liberated from the real world.

ALICE UNCHAINED is also one of several works purchased by the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York. It also ended up on the cover of curator Christiane Paul’s history of digital art.

AM: You have always been an artist of your time. How do you see the present?

CH: I continue to push my same approach into the future. As a new present endlessly unfolds, often in unpredictable ways, I am still trying to connect the dots of a larger history and of my own history to the present.

My general approach is to spin what ends up being very cerebral mythologies about technology. I’m very lost in my thoughts, and I actually think that my virtual version of visionary architecture frames my consciousness. I fall into 3D Cartesian space and experience it as a model of my brain. This is an intellectual love story that’s lasted a long time. So when I was invited to produce generative art for an Art Blocks drop earlier this year, I decided to keep with my long project. I was already doing DIGITAL COMBINE paintings, so I decided to dive again into painting, but using Art Blocks technology. Andrew Blanton, my old friend and collaborator who is both a composer, a virtuoso drummer, and a digital prototyper, collaborated with me on SYSTEMS MADNESS for the platform.

SYSTEM MADNESS is flat, meaning it wasn’t created in 3D spatialized software. With Andrew, I translated digital painting in a different way. The story I tell with this work is, as always, one of visions and visionaries. This theme governs the “Body” half of my split “body/mind” art practice. The Machiavelli and the aphoristic NFT works are my dialectical “mind” sides.

SYSTEMS MADNESS was inspired by the short story THE YELLOW WALLPAPER (1892) by Charlotte Perkins Gilman. The project uses AI tools to transform literary language into a library of visual tropes, a translation of emotional expression into code. We reconstructed the pattern language of romantic era wallpapers, using warm, off-primary colors, noises, gradients, blurrings, and layerings, by applying different fractal formations, repeated like systematic wallpaper that slowly deforms if you interact with them but also if you don’t. The wallpaper patterns we created are highly irregular because Andrew encoded irregular, random deformations into what started out as regular, repeat patterns. I thought of them as expressing the very human need to create order out of chaos. Andrew also developed five poisonous flowers, all organically evolving and flowing like miniature lava lamps. The ones pictured here are Poppies and chrysanthemums, both of which are poisonous in the real world and induce hallucinations if you add them to your salad.

Together, Andrew and I framed a question: What happens when reason meets unreason? The response: Too much order will drive you mad. And frankly, I hope I haven’t driven YOU mad with this very long story. Just think—this is only about a third of it. So thanks many times over for your incredible patience, dear Anika.