Elliott Burns has interviewed Aaron Scheer about his favourite artists and inspirations.

In conversation with…Aaron Scheer

By Elliott Burns

Elliott Burns: So I’d like to begin by getting a sense of what makes the correct atmosphere for artistic production; for you. Not in general.

Aaron Scheer: I need to be in a tunnel, where I shut off all factors that are hindering my creative production. The optimum state would be a creative flow, being fully deployed in the moment, where tacit practice is taking over. These moments are rare though. Sometimes they happen, sometimes not. Nevertheless, I don’t want to provoke the feeling that you just have to wait for the right moment. It’s the opposite in fact. I try to force those moments. And that means a lot of hard work and late night hours.

I’m a workaholic, I guess. Fast experimentation and production is crucial. It helps me to develop. It’s also part of my overall work, I guess. The process becomes the artwork. The right music and black tea helps me to get it started. I’m using some kind of rituals, where repetition is integral, for example when I listen to electronic music. It sets me in some kind of trance, where I ideally can blend out distracting, unnecessary external and internal factors at that very moment.

EB: It sounds like you’re aiming for a balance between a ‘mechanical’ and a ‘human’ approach?

AS: Doing things all over helps to automatise, things are just flowing, they are coming somehow natural into being. Repetition also helps to perfect your craft. The mechanical production that you’re mentioning does play a part in my work, because it’s still playing an important role in our lives. Especially as sophisticated technology, such as algorithms and advanced robotics, starts to infiltrate our daily lives.

At the same time, more and more people feel pressured to think and act like machines. Always faster and better, while consuming less (mainly financial) resources. Machines are dictating nowadays how we live. And we start to not being able to keep up with that pace anymore. Because yes, we’re still mainly human. But might be hybrids in the very near future.

Technology might be the next evolutionary step in human mankind. I want to reflect that discourse in my work. I want to see what it does to my work. I want to discover the human in technology, and the technological in the human. What does contemporary industrial production make with a highly individual and human product, such as art? I’m interested in that question.

EB: What are your top five technologies (hardware or software)?

AS: 1. MacBook Air

- Smartphone

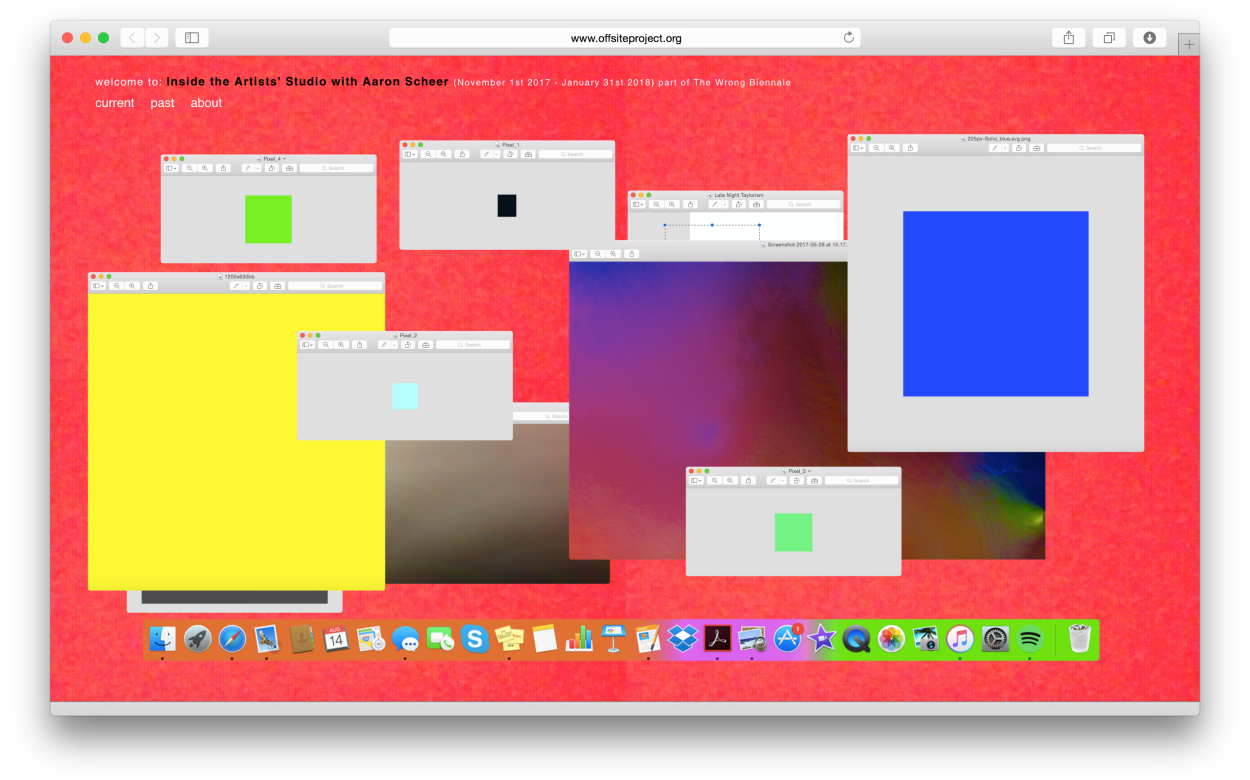

- Screenshot (More of a command than a software, still very important to me)

- Gmail

- Instagram and YouTube

EB: Aspects of your practice could be called ‘photorealistic’, such as the Screenshot series; others, abstracted colour studies, resemble experiments by Wolfgang Tillmans. How do you characterise your work’s relation to photography?

AS: Art critiques, curators, even other artists are often making that connection. I don’t see myself as a photography-based new media artist, rather as an interdisciplinary artist in a digital age combining different techniques, mediums and streams. Photography is included, is one part, but not the sole focus of my work.

I like the instant character with the medium of photography. Something happens and you can immediately document it. It feels natural, true and honest that way. I guess that’s the enigma around Snapchat. At the same time, photography can be extremely staged and rigorously planned in every little detail. Post-production, for example through Photoshop, adds the last artificiality to it. Reality and fiction get ultimately mixed up. Those two worlds somehow collide in Tillmans’ work. Most of his photographs seem like snapshots of his environment, but at the same time all of his works are complex compositions of colour, form, angles and light, and have somehow a staged character to it. Tillmans manages to combine worlds within his work, the instant and the arranged, the natural and the artificial, the contextual and the beautiful, the realistic and the abstract. It makes his work multi-dimensional. That’s what I like about his work so much.

If I don’t like one thing, it’s one-dimensionality. It’s a simple formula: one-dimensionality = boring; multi-dimensionality = interesting.

EB: How about the current ‘look of art? I’m speaking in relation to how elements of our digital lives are increasingly making their way into art. Have we become too enthralled by the veneer of digital culture? Is it having a homogenising affect?

AS: I personally like and promote the new aesthetic direction that art is taking, especially with all its vibrant colours. A good time for colour theorists.

The new look can be overloaded and much too loud, but that’s just simply reflecting the world we’re living in. But it’s interesting that you’re mentioning the digital as some kind of aesthetic code. If you consider the digital as being intangible, a space built around software, highly abstract, the digital is a priori neutral. It gets an aesthetic code when interface designers chose colours, forms and fonts. The digital is something that is man-made, it’s socially constructed; it’s not nature.

That ultimately means that corporations, respectively individuals within corporations, decide how the digital looks like. They define the aesthetic that dominates the digital and set new trends. We’re not getting inspired by our natural surroundings anymore, but by a corporate and socially constructed intangible digital space, which is slowly replacing nature; it’s becoming nature, somehow.

In that respect, the spheres of art, design and business are highly connected. I’m reflecting this relationship in one of my latest series, where I investigate corporate branding / marketing and design, in an aesthetic space that could be both inspired by nature and our new nature, that is the digital.

EB: And by corporate branding in relation to the arts I think we know we’re typically speaking about Apple. You, me, likely everyone reading this will be on a Mac or iPhone.

AS: I have mixed feelings. On the one hand, it’s my own choice, what I’m working with, and what I take as inspiration or not. At the same time, no one can argue that it does have an influence, when the majority of creatives are working with specific products and software. And with it comes a certain aesthetic, no doubt. Nevertheless, it’s up to us how to deal with that. You can either celebrate it or hack it. I’m somewhere in between, as always.

EB: You said your latest series of pieces, one of your latest, is taking up these issues?

AS: What I do think is that if you want to move something in this world nowadays, it’s connected to business. And that means it’s connected to corporations. Just consider the development in Silicon Valley and the internet. What was once an utopian alternative hippy movement that wanted world peace and locally produced organic food for everyone, has turned into the most powerful corporations in the world. The creative industry, including the arts, is now interwoven with the corporate world. We’re part of it, no doubt. Capitalism has swallowed the social and artistic movement that was going on in the late 60s and early 70s and has made it their own. A new form of artistic and social criticism needs to be established that fights against the increasing and alarming disparity in our society.

EB: Which five contemporary artists are you looking towards?

AS: 1. Cory Arcangel

- Ry David Bradley

- Anders Clausen

- Artie Vierkant

- Signe Pierce

EB: Your current inkjet and oil crayon series, these are hybrids, one part digital, one part analogue, with an aesthetic referencing abstract expressionism but also the digital abstract. As digital images, online, they feel exact; the paper versions look floppy, saturated and fragile. If feels like a lot is happening here between the ‘digital’ and the ‘real’.

AS: My experimentation between the poles of analog and digital, plays the most important role in my recent work. It’s the attempt to build bridges between the two. To wander between different worlds, in order to test out and stretch boundaries. Ralf Hanselle, profiled art critic from Germany, has been describing me as being a cross-border commuter, constantly searching for confrontation and transformation, in the search for something new. I like the tension that is being created through this kind of conversation. It gives my works a certain depth, I think. Plus, I can’t entirely give up on physicality. I like the smell of acrylic colour. I like to touch the smooth surface of my inkjet and oil crayon pieces. I like to see my works in a physical space. A lot of magic is still happening for me through experiencing art in a physical, tangible space.

EB: How about the reverse, when the ‘real’ goes online, like in Instagram. From what I can tell you use it a lot. Most artists I know do. The platform is ubiquitous with the dissemination of art, integral to networking and following new trends. What’s your relationship with it like?

AS: Yes, Instagram. A topic that seems to be inevitable to the arts, at least at this point. For me, I have a strong relationship with Instagram. It helps me spread what I would like to convey, both conceptually and aesthetically. Well curated content, in combination with strategically trying to build networks, in the digital, but also the ‘real’ world, through Instagram, is also being one of the reasons why I’m getting attention from a certain circle. And I’m trying to use it the right way. And I won’t lie, I’m also using it to keep myself informed of what’s going on out there and what kind of things work out, and what not, at least online.

Doesn’t mean that I’m choosing which works to go for with galleries, or exhibitions, due to the amount of likes on my Instagram; but it’s at least some kind of indication. Also regarding the audience. You can learn a lot from these things. And why not using this information? Doesn’t make sense to me. Nevertheless, I’m always strictly curating what feels right to me. For example, my first gallery contact wanted to have only digital paintings in the gallery’s catalogue, but I insisted on including rather “difficult” works, such as my smartphone and screenshot pieces, as well as some of my conceptual printer pieces. And it has been included. Maybe not the smartest commercial decision. But it helped me to evolve.

And that is always more important. (I hope you will remind me of my words one day, in case it is needed). Likes and follows are becoming the new currency of our society. Yes, think Black Mirror style here. And am I using intelligent algorithms to boost my likes and follows? No. I’m rather becoming the robot by myself. Chose which one is more questionable.