Art in America contributor, the writer and curator Legacy Russell, has profiled the virtual experience works of Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley to show the dangers of “trans tourism” and how “building an archive is a trust exercise”.

How Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley Archives the Black Trans Experience

By Legacy Russell

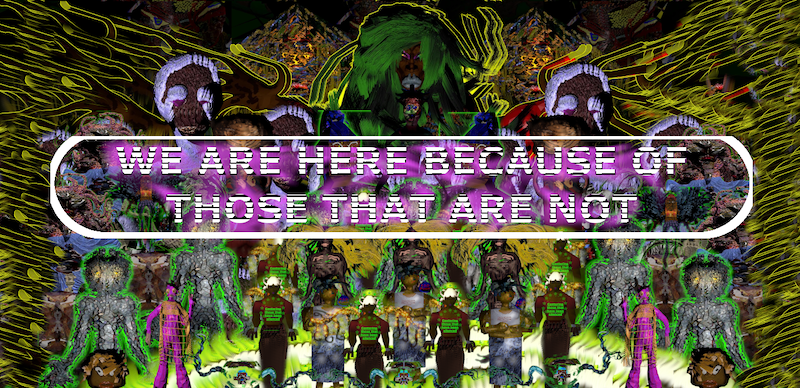

Building an archive is a trust exercise. This is what Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley—a Black British trans artist and game developer—teaches us. The Berlin- and London-based artist says she aims to compile the narratives of Black trans individuals—“those living, those who have passed, and those that have been forgotten.” Her works, which live on the internet, are often referred to as “games,” though perhaps “virtual experiences” is a more meaningful identifier. Although Brathwaite-Shirley employs gaming technology and infrastructure, she also actively refuses the gamification of Black trans identity. Embedding prompts and questions that push participants to examine the harmful and voyeuristic practice she calls “trans tourism,” the artist positions her archive as a central meeting place, a homecoming site for Black trans people, where their stories can be stored and celebrated.

In each virtual experience, Brathwaite-Shirley, who graduated from the Slade School of Fine Art in London in 2019, establishes a social contract. In dialog boxes, she details rules of engagement between the artist, as game developer and host, and the user, as guest and participant. As I write this, I Can’t Remember a Time I Didn’t Need You (2020) is featured on her website’s homepage. Its floating banner reads THEY SAY YOUR LIFE MATTERS, and visitors receive a prompt: CLICK HERE TO ENTER THE CITY OF DREAMS. Amid an animated, pixelated cityscape reminiscent of the 1990s web hosting services Geocities and Angelfire comes a disclaimer (THIS ARCHIVE CENTERS BLACK TRANS PEOPLE. THOSE THAT ARE NOT BLACK AND TRANS MAY FEEL UNCOMFORTABLE) and a trigger warning (TW: THERE ARE THEMES OF LOSS WITHIN THE ARCHIVE).

Respecting the terms of Brathwaite-Shirley’s space, I can tell you only so much about my experience. Before entering City of Dreams, visitors encounter a dialog box that asks for their name, and it’s impossible to bypass this inquiry. Visitors to Brathwaite-Shirley’s digital territory might rightly wonder, who is storing this data? How will it be used? The simple prompt “What is your name?” can be complicated, triggering, and empowering all at once for Black and trans people. Today, many Black people still carry the last names of those who once deemed us their property. Some Black and queer people have emancipated ourselves with names of our own choosing. These self-determined names designate our chosen families, which house us and keep us whole. Typing our name online returns us to our body off-screen.

As I move through Brathwaite-Shirley’s online city, I think of the banner she showed me earlier on the virtual road: REMEMBER YOUR IDENTITY IS RESPONSIBLE FOR ALL YOU WILL EXPERIENCE. This reminder rings true both on and away from the prosthetics of our machines. Though Brathwaite-Shirley carefully guides me through this space, providing comforting prompts and a clear path, I still find myself deeply alone in the pixelated fog. Visitors are free to wander into different areas, and I found myself in places of queer nightlife or worship that left me longing for congregation. Within these sacred spaces, Brathwaite-Shirley prompts us to utter confessional mantras aloud, granting forgiveness to others and pledging self-care to our screens. Throughout, Brathwaite-Shirley deftly and generously negotiates the complex dialectics of voyeurism and witness, spectacle and participation. As I step into the virtual streets of her city, I heed Brathwaite-Shirley’s words: REMEMBER TO TAKE MOMENTS / TO ACKNOWLEDGE WHAT YOUR EXISTENCE MEANS.